Mowgli:

In fact a recent newspaper article made the rather astonishing claim that Disney’s Jungle Book is the fifth most watched film of all time, with an estimated cinema audience of 353 million! That’s pretty incredible by anyone’s standards, and it’s not even counting video releases or TV screenings. With subsequent DVD and Blu-Ray releases it’s a complete no-brainer that the total has increased still further. (And I suppose it’s not surprising given Disney’s current outbreak of sequelitis [Return to Neverland, anyone???] that they went and made The Jungle Book 2...sigh.) But just to make it perfectly clear once more: that’s not the version that inspired the Ketrin stories, but the original by Rudyard Kipling. For information on Kipling I suggest you visit The Kipling Society. According to Kipling himself, the “Mow” of Mowgli is supposed to rhyme with “cow”. Disney changed the pronunciation to rhyme with “flow”, I guess because the original was too similar to (Chairman) Mao, who wasn’t very popular in America at the time. But then, Disney made so many changes to the story that Kipling would hardly have recognised it. There is no way you’d ever catch the original Mowgli (or Ketrin) wearing bright red shorts - they’re not exactly good camouflage, for one thing - or singing silly songs. The fact is that Disney’s version has ABSOLUTELY NOTHING TO DO with Kipling’s original story, aside from the characters’ names and species and a couple of isolated incidents. In fact I’d go so far as to say that Disney’s Jungle Book was the worst thing that ever happened to Rudyard Kipling’s literary reputation. (I was about to say it was the worst thing that happened to Kipling, but probably the worst thing that happened to him personally was losing his son in the Great War.) Now, I don’t want to knock Disney too much - they did revolutionise animation and bring entertainment to millions, after all, and they’re still at the cutting edge of animation technology (although rivals like DreamWorks are now snapping at their heels). But the debate about Disney’s ‘vulgarisation’ of classic stories was never louder than when their version of The Jungle Book was released. For instance, the Disney version contains lots of cute talking animals, but completely glosses over the fact that in order to survive they have to kill and eat other cute talking animals! Kipling himself certainly doesn’t ignore this point - see his story “How Fear Came” in The Second Jungle Book, which features lots of barbed banter between predators and prey during a ‘water truce’. Also, as I’ve pointed out elsewhere, any film version of The Jungle Book should logically be called The Jungle Movie!!! Another unnecessary change that Disney made was to turn Kaa the snake into a villain, presumably because the American public just doesn’t like snakes. Remember what time period we’re talking about here - it’s 1967, the Civil Rights Movement is at its height, and yet Disney are making a character a villain solely because of his ‘race’ !!! In the originals, Kaa is quite a civil serpent (sorry). He’s actually like some kind of cold-blooded alien: it may be nice to know he’s on your side, but you’ll never really understand him. There’s a terrific scene in “Red Dog”, in The Second Jungle Book, in which Kaa enters a trance so that he can search his century-long memory for strategic information. When he wakes up, his words are bewildering to Mowgli:

Eat your heart out, Walt. It would be nice to have a character as strong as that in the Ketrin series, but in all honesty I don’t believe I could get close to that level of writing. In fact there is a scene in “Kaa’s Hunting” in which Kaa hypnotises a troupe of monkeys so they can’t move without his command, but Mowgli is immune to his spell because he’s human - another important plot point that Disney ignored. There have been various other film, TV, comic book and even radio versions of The Jungle Book, but for my money not one of them has ever managed to capture Mowgli’s blend of wildness and innocence - even naïveté - which is why I’ve tried to bring out those characteristics in Ketrin.

In Kipling’s original stories Mowgli is totally naked (right) while growing up in the jungle because he’s never heard of clothes. Of course, his nakedness also symbolises his lack of natural defences against tooth and claw. Later he returns to the human village and learns all about clothing, but it isn’t long before human society rejects him because of his wildness (and lack of hypocrisy), and so he goes “back to nature” in every sense of the word. Although he then chooses to be naked, that doesn’t make him a nudist as such,because he doesn’t do it for health or ideological reasons. It’s just what he’s used to, and most comfortable with. Besides, there are no laundrettes in the jungle. Mowgli’s nudity has always appealed to me, not for paedophile reasons, but because I love the idea of being wild, free and naked in the jungle. (I also love the idea of having lots of big, powerful animal friends.) That’s why in my own stories Ketrin shares Mowgli’s lack of hangups about nudity, alongside his taste for raw meat and his instinctive hatred of injustice. In reality I guess beng naked in the jungle wouldn’t be quite as glamorous as it sounds - there’d be all sorts of nasty biting insects, plants with strategically-placed thorns, and pointy rocks to contend with for starters. But I guess that’s nothing compared to fighting tigers and wild dogs.... There is one tiny difference between Mowgli and Ketrin that’s possibly just worth mentioning: as far as I can tell, Mowgli is heterosexual - or rather, he will be when he’s old enough.

Eyton’s wild boy, Nanga the Naked One, is very different from Mowgli (apart, obviously, from being naked). For one thing he never speaks, although his actions speak loudly. But there is a tiger, an evil and cunning old beast that we know the boy must one day fight to the death. There is also a corrupt moneylender whose beautiful daughter is growing tired of his abuse, and it can surely be only a matter of time before she runs away and meets the wild boy and both of their lives are changed forever. The book’s plot is driven entirely by bizarre coincidences, which makes it all hugely implausible but lots of fun, and you can now read it here. Alternatively, if you’d prefer a dead tree edition, you might try searching on Bookfinder.com. Editions with dustjackets are rare and far too expensive, but I’ve found a picture of the cover artwork, shown below alongside another wild boy novel, which I’ll get to in the next paragraph....

For instance, at a local second-hand bookstore I recently happened to discover another forgotten wild boy novel: Shasta of the Wolves by Olaf Baker (Dodd, Mead and Company, Inc., New York, 1919; George C. Harrap and Company, Ltd., London, 1921, illustrated above.) In this entertaining if slightly long-winded novel, Shasta, a baby lost by a Red Indian tribe (as they were called in those innocent days before Political Correctness) in the mountains of the American northwest, is discovered by a she-wolf who is inspired by the “spirit of the wild” to raise him alongside her own cubs. Growing up in the wild, Shasta witnesses a great chorus of wolves (a bit like Kipling’s Toomai witnessing the dance of the elephants), takes revenge on an eagle for stealing wolf-cubs, and is finally persuaded - by a medicine dance and the smell of cooked meat - to rejoin his human birth-tribe, and to wear clothes (although he insists on keeping his legs bare for the sake of mobility). It turns out that Shasta was deliberately abandoned to the wolves by an enemy tribe after a raid many years before. Some time after Shasta’s return to human society that same enemy tribe attacks again and Shasta is captured as a human sacrifice. Narrowly escaping with the aid of the wolves, he then turns the tables by setting the entire wolfpack upon his captors. Text now available on-line

There’s also a subplot about her discovering a glass bottle - possibly a nod to the film “The Gods must be Crazy”. Like Mowgli, Nanga and Shasta, Pyrénée is naked, but of course it’s perfectly innocent. Even so, I can‘t imagine Pyrénée being reprinted in America - the Land of the Free, except when there’s the slightest hint of nudity!.... There’s a full page about Pyrénée on the Wild at Heart site.

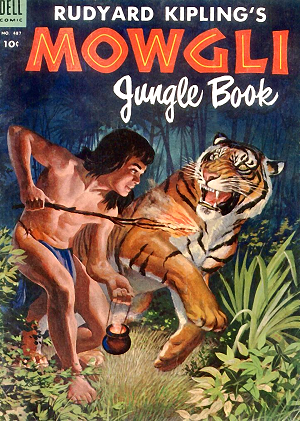

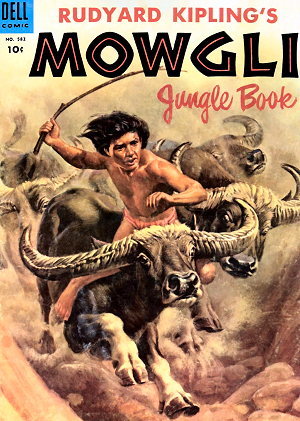

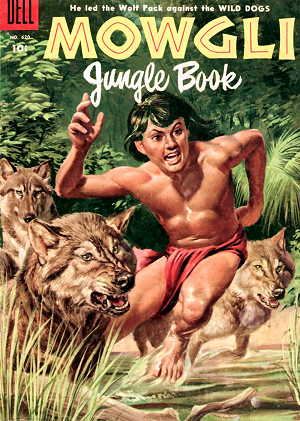

Between 1953 and 1955, the long-running Dell Four-Color Comics series featured Mowgli in three issues (#487, #582 and #620), with beautifully-painted and dramatic covers. I’ve now established, through Readers could hardly claim they weren’t getting value for money, because there was no advertising and the story occupied all the interior pages and both sides of the back covers (although the inside back covers are in black and white), making a total of 34 story pages per issue, 102 pages all told. The first Mowgli comic, Dell #487, is based on the first two stories in The Jungle Book, “Mowgli’s Brothers” and “Kaa’s Hunting”. In the original chronology, “Kaa’s Hunting” takes place between the first and second halves of “Mowgli’s Brothers”, so in the comic version the events of “Kaa’s Hunting” are sandwiched between the two halves of “Mowgli’s Brothers” to form a single narrative. The second Mowgli comic, Dell #582, is divided into two halves, based on “Tiger! Tiger!” from The Jungle Book (retitled “Mowgli and Shere Khan” in the comic), and “Letting In the Jungle” from The Second Jungle Book. The third and final Mowgli comic, Dell #620, also contains two stories, “Red Dog” and “The King’s Ankus”, reversing the chronology of the original stories from The Second Jungle Book. Two of the Mowgli stories from The Second Jungle Book are not included in the Dell adaptations. “How Fear Came” is a jungle legend that is told to Mowgli, so it doesn’t quite fit in; and “The Spring Running” winds up the Mowgli series, so maybe the comic publishers thought it was better to leave the story open-ended. Some of the original violence has been toned down, but otherwise the comics follow the books’ original plots fairly closely - apart, of course, from the fact that Gollub gives Mowgli a loincloth. Trivia note: the loincloth is blue on the first cover but red on the other covers, and also red in the interior art. This version of Mowgli doesn’t seem to have learned about camouflage either!

Comment on this article | Return to Top of Page | Home | |||||||||||||||||

y character

y character

bviously the various visual adaptations, including

bviously the various visual adaptations, including

hile the Jungle Books are deservedly famous, several other stories about children raised by animals have languished in undeserved obscurity for decades. For instance, while researching Kipling I happened to come across references to a forgotten adventure novel called Jungle-Born by John Eyton (Arrowsmith, London, 1924; The Century Company, New York, 1925), which features a feral boy raised by apes in northern India.

hile the Jungle Books are deservedly famous, several other stories about children raised by animals have languished in undeserved obscurity for decades. For instance, while researching Kipling I happened to come across references to a forgotten adventure novel called Jungle-Born by John Eyton (Arrowsmith, London, 1924; The Century Company, New York, 1925), which features a feral boy raised by apes in northern India.

reat though the internet is for finding obscure and out-of-print books, it’s still nice to physically unearth some interesting volume lying neglected on a dusty shelf. By reading such a “lost” book, I feel as if I’m rescuing its words from eternal oblivion.

reat though the internet is for finding obscure and out-of-print books, it’s still nice to physically unearth some interesting volume lying neglected on a dusty shelf. By reading such a “lost” book, I feel as if I’m rescuing its words from eternal oblivion.