Ketrindex Prologue Part One Part Two Part Three Part Four Part Five Part Six Part Seven Part Eight Part Nine Part Ten Part Eleven Part Twelve Part Thirteen Part Fourteen Part Fifteen Part Sixteen Major Players Kipling and Ketrin and Mowgli and Me  Jaskri and the Maiden Jaskri’s Child The Sculptor’s Model Adrift |  Copyright © 2014 by Leem This story may be posted on other sites provided that all of its instalments to date are posted, that Leem is identified as the author, and that no unauthorised changes are made to the text Previously on Ketrin... In Part Thirteen: Trapped in the Valley tunnel, Tharil’s and Mavrida’s groups were slowly suffocating until an apparent miracle occurred, transporting them thousands of cubits to safety. Once recovered, they set off in what they hoped was the direction of Third Hill. En route Suvanji freed a paralysed wildling boy who had lost a leg, naming him “Three-Leg” for his tripedal locomotion. Then Sherinel’s party stumbled across them, and the combined group arrived at Third Hill in good spirits. Tolar was reluctant to let Mavrida free Ketrin, so she paralysed him, only to re-encounter three hostile strangers, now armed by the sorcerer with lethal spells. Aided by a presence in her mind, Mavrida disarmed and paralysed the men, and after some initial difficulty released Ketrin from his long paralysis. She and her new friends waited outside the shrine while Ketrin and Sherinel made love, and the Maiden appeared to warn them that the sorcerer would soon attack. |

Peri-feral Thoughts

Skip to Story

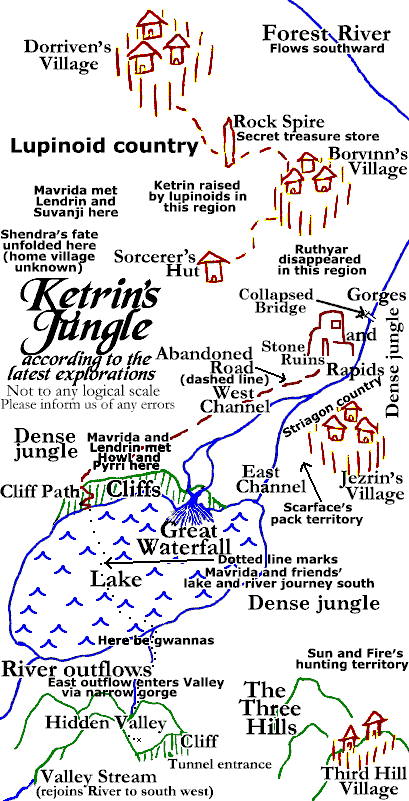

The story takes place several hundred light years from Earth in about AD 3502, give or take a century or three.

Omnes Ketrin and Sherinel eventually emerged from the shrine, followed by Silverpaw and Shadow. Ketrin sighed and stretched, letting the warm rain wash the sweat and seed from his naked body. “Oh, it’s so good to feel the rain,” he intoned languidly. Mavrida smiled and hugged her son. “It’s good to see you on your feet again, Ketrin,” she said. “But now I need to borrow your knife for a little.” “My knife?” said Ketrin, puzzled. “That’s right. Tolar was getting stubborn so I’m afraid I was forced to paralyse him with my jewel, but I can’t use it to free him because it burned out when I freed you. If I can’t free him with your jewel, the entire village will want our heads.” Ketrin still did not fully understand how the jewels worked, but he knew he could trust Mavrida to use them wisely and so handed her his knife without hesitation. To Mavrida’s relief the blue crystal in the knife-hilt was still glowing as brightly as the others. Turning to the paralysed Jeylin, Sarlin and Jerrond, she said, “I’ll have a word with the chief hunter about what we should do with you. Assuming he doesn’t evict me for the little prank I played on him.” By the time Mavrida and her companions arrived back at Tolar’s hut, a small crowd had gathered. Tharil was apparently attempting to pacify them, while Kemmet attempted to shout him down. Seeing Mavrida’s party approaching the crowd surged forward, goaded on by the surly archer. Silverpaw, Shadow and Nipper bristled, and had to be restrained by their two-leg friends. “Please let me through,” said Mavrida. “I’ve come to free Tolar, and I can’t do that if you’re all standing in the way.” “Oh, yes?” said Kemmet. “And how do we know you haven’t come to kill him?” Mavrida rolled her eyes. “Why should I want to kill him?” she said. “I only froze him because he wouldn’t let me unfreeze my son. Now, as you can plainly see, Ketrin is unfrozen, so there’s no need for Tolar to remain so either.” Tharil took the opportunity to jump in. “She’s right. Come on, now, the sooner you let her through, the sooner she can free Tolar.” “Then what’s she doing with that knife?” Kemmet demanded. “You think I mean to cut him?” replied Mavrida. “The spell that can free him is in the hilt. All I need do is bring it close to Tolar’s body and he will be free to move.” “Well, if it’s that simple, why can’t we do it for you?” Kemmet sneered. “Because,” she said, “the spell is in my charge, and it’s my son’s knife.” Besides, she thought, I’d be mad to let Kemmet get hold of the spell! “Now,” she went on, “if you’re not getting impatient to see Tolar freed, I’m quite sure he must be by now. Do you think he wants to listen to more of our arguments?” “She’s right,” Tharil reiterated. “Stand aside, Kemmet, and don’t forget that I’m still second hunter of this village.” Kemmet grumbled, but did as he was bid. “All right, Mavrida,” said Tharil. “You may approach Tolar, but remember to keep your hand away from the knife-hilt at all times.” Mavrida nodded and walked over to where Tolar stood frozen. She noticed that a lock of the chief hunter’s dark hair was draped over his shoulder, concealing the crystal that was paralysing him. Very clever, Tharil, she thought. Thank you. Holding the knife by the tip of its sheath she extended the hilt toward Tolar’s shoulder and thought, +MOVE!+ The crowd gasped as Tolar’s body spasmed momentarily. Meanwhile Mavrida surreptitiously snatched the crystal from beneath Tolar’s hair. “I’m all right,” cried Tolar. “I am unharmed. Mavrida has freed me, just as she said she would.” “Yeah, but she was the one who paralysed you in the first place,” shouted Kemmet. “Thank you, Kemmet,” said Tolar, “I’m well aware of that. And I see that against my express wishes she has freed Ketrin, our living representative of Lord Ral-ne-Sa. The question is, what should we do about it?” Surprisingly, it was Erennya the midwife who spoke in reply. She had emerged from her hut a few moments earlier to see what all the fuss was about, with Pyrri, Three-Leg and the lupinoid Howl in tow. “If Ketrin really is Lord Ral-ne-Sa’s mortal embodiment,” she said, “then he should be allowed to speak... now that he is at last able to do so.” All eyes turned expectantly toward the beautiful naked youth, whom hitherto most of the villagers had only seen (and felt) sitting or lying motionless. Despite having been mute for so many moons his voice was clear and resonant. “I don’t believe Lord Ral-ne-Sa ever intended me to remain frozen permanently,” he said. “Well, that’s just what we’d expect you to say,” said Kemmet. “Maybe so,” countered Tharil, “but what does Lord Ral-ne-Sa say now, Ketrin?” Ketrin sighed. “I haven’t been able to hear him lately...” he began. “I knew it,” growled Kemmet. “He’s a fraud. He never was Lord Ral-ne-Sa’s chosen in the first place.” “Oh, so he got himself paralysed deliberately, you think?” replied Tharil. “Lord Ral-ne-Sa has spoken to me often,” Ketrin insisted. “What I’m trying to tell you is that since recently something has been preventing him from contacting me. There is another power at work. Something dark and cold.” “Oh, come on,” groaned Kemmet. “It’s true,” said Mavrida. “I have encountered it. It looks like an old man in rags, but it’s really an evil and powerful god, so powerful it can even prevent the Maiden and Lord Ral-ne-Sa from speaking to us. So far by their grace we have managed to escape its clutches, but I feel in my bones that it’s not done with us yet.” “All the more reason we should be rid of you all now,” said Kemmet. “Maybe if you were all gone - or dead - this evil god or whatever won’t bother us.” “Don’t you believe it,” said Lendrin. “You can’t avoid evil by just hoping it’ll leave you alone. No matter what you do, the old man’s sure to attack Third Hill sooner or later.” “Three of his cronies have already tried to attack us,” said Mavrida. “That was one of the things we came to tell you, Tolar. Luckily I was able to paralyse and disarm them before they did any harm.” “Three intruders, you mean?” said Tolar. “Inside Third Hill? How did they get past the guards?” “Sorcery,” Mavrida replied. “The old man transported them here somehow.” “So what’s to stop him sending a hundred men next time?” demanded Kemmet. A pertinent question for once, thought Mavrida. Aloud, she replied: “I don’t think he has the power to send that many, even if he had them. Not yet, at least.” “All right,” said Tolar, “one thing at a time. These intruders, Mavrida, they’re still paralysed?” “Yes, Tolar. They’re outside the shrine.” “Well, then,” he said, “we can leave them to stew for a while. As for the threat, if there’s no telling where it’s coming from then there’s nothing we can do except remain vigilant for anything unusual.” “Right,” growled Kemmet. “Like lupinoid people and miraculous rescues and paralysing spells are usual.” Tolar sighed. “All right, Kemmet, I believe you’ve made your opinions clear. For my part, I don’t believe Mavrida and her friends are responsible for alerting this evil to our presence. If anybody should be blamed it’s me, for bringing Ketrin into the village in the first place. Yet if it hadn’t been for Ketrin and his influence on the lupinoids we’d probably all be dead from starvation by now.” Kemmet looked sceptical, but wisely chose to remain silent as the rest of the crowd was nodding in agreement with Tolar. “Anyway, as I was saying, right now all we can do is remain alert for danger. In the meantime, our hunters and their guests have brought us plentiful supplies of food, so I suggest we hold a feast to welcome Sherinel and Mavrida and their friends, and also to welcome Ketrin back to the world of mobility.” A cheer went up from the crowd. “Nothing like food to take their minds off the negative,” muttered Lendrin. While Tolar had been speaking, a young man had emerged from one of the huts and made his way over to the crowd to see what the fuss was about. Seeing Ketrin standing alongside Sherinel, he gasped and ran forward. “Lord Ral - I mean, Ketrin,” he began. “You - you’re standing! I mean, you can move!” Ketrin embraced him intimately. Some of the villagers discreetly averted their gaze. “Yes, and I’m very happy about it,” he replied. “Not that I was unhappy about your visits. Sherinel, this is Wersgor, one of my most enthusiastic worshippers.” Sherinel also embraced the youth, saying, “I’m glad you kept him company all this time. I guess we have something in common - I’m what you might call Ketrin’s first worshipper. Maybe the three of us can get together sometime soon.” Tolar cleared his throat. “Yes, well, I hope when you do so, it’ll be somewhere a little less public,” he said. Casting a brief downward glance, Ketrin said, “Ah, yes. Forgive us, chief hunter. We were getting a little excited there, weren’t we?” Tolar smiled and nodded. “We must see about providing clothing for you and Sherinel and your wildling friends. Right now, though, we have a feast to prepare, and then we’ll see about providing living quarters for you and the rest of our new guests.” Kemmet muttered something uncomplimentary and slunk away. Few were unhappy to see him go. While Tolar and Tharil began making plans for the feast, those of Ketrin’s and Mavrida’s companions who had not already done so made their acquaintances. True to Tolar’s word, garments were soon found for Ketrin, Sherinel and the wildlings. Telepathically, Ketrin told Sherinel that he would only wear clothing within the village as a concession to local customs. Sherinel agreed, telling his friend that since he could now think like a wildling he might as well behave like one, and had in any case grown accustomed to nudity. Erennya, Sherinel and Suvanji bathed the wildlings in warm water, washed their hair, and gave the men waistcloths and the women simple dresses. The wildlings found clothes a little harder to adapt to than Ketrin and Sherinel. Sherinel persuaded Keino and Wenric to don them just to keep the two-leg pack happy. When Lendrin tried the same for Three-Leg and Pyrri, he could feel their annoyance at the thought of not being able to reach between their legs whenever they felt like it. +You’re not supposed to do that right now anyway,+ Lendrin reminded them. +Look, you can do it when you’re alone, and apart, and when the villagers can’t see you. All right?+ Reluctantly they agreed. The wildlings were also dubious about the idea of haircuts, even when told that shorter hair would be more convenient. Pyrri, who had most to lose, was unhappiest at the idea, but had no choice but to comply. Eventually, amidst much squirming and fidgeting, Erennya managed to trim Pyrri’s luxuriant cloud of hair to a more manageable shoulder-length, then she rinsed, dried it and laboriously combed it with much squirming from her charge. When she was finished, Pyrri stared mournfully at the large pile of trimmings as if it were a severed limb. Erennya found her a colourful dress and showed her how to put it on. As far as body coverings were concerned, Pyrri considered cloth a poor substitute for hair. “Oh, you look really nice,” Mavrida told her, when she presently emerged into the daylight. Pyrri gave her a dubious glance and muttered, “Feel all wrong. We gonna soon eat?” “Yes, we’ll eat soon,” said Lendrin with a sigh. Turning to Mavrida, he said, “She’ll get used to it.” “At least her grammar’s improving,” Mavrida replied. Since none of the huts was big enough to accommodate all of the newcomers and the villagers who wanted to meet them, the hunters converted two of the largest tents into a canopy that covered much of the village’s central area, and placed mats on the ground. The surly Kemmet stayed away, but most of the other hunters attended along with spouses, partners and invited guests. Ketrin had the honour of sitting beside Tolar, with Sherinel beside him and the rest of the newcomers close at hand. The evening was a great success. The majority of the villagers warmed to the strangers as they had to Suvanji, fascinated by the stories of their daring exploits. “Just as well Kemmet stayed away,” whispered Lendrin to Mavrida. “He’d probably say we’re making it all up, even though he was there some of the time.” At the same time, however, their news of the old sorcerer had already circulated around the village, causing considerable anxiety. “The trouble with the sorcerer,” Lendrin told the diners, “is his unpredictability. We have no idea what his powers are or where he’s planning to strike next.” “And his motives are also a mystery,” added Sherinel. “Why has he been paralysing wildlings and lupinoids? Does he think they’re a threat to him? If so, why didn’t he just kill them outright?” “Maybe he was trying to torture us,” said Suvanji, “drive us insane. Except... we didn’t go insane. It’s like the crystals were made to keep us calm and relaxed the whole time. Strange that the sorcerer wouldn’t know that.” “Perhaps he was just saving us for later,” said Ketrin. “Preserving us for something worse.” “That’s all very well,” said Tolar, shaking his head. “All this speculation doesn’t get us anywhere, let alone suggest a meaningful course of action.” “Seems to me our only course of action is to remain vigilant,” said Tharil. “Keep ourselves alert for anything unusual.” “Kemmet would say that’s us,” said Lendrin. “Well, that’s unusual for a start,” said Tolar, nodding toward Pyrri. The wildling was rolling her head up and down and from side to side in a curious fashion. +“Pyrri, stop that,”+ said Lendrin, both telepathically to Pyrri and aloud for the benefit of the villagers. +“You’ll make yourself dizzy, and we don’t want you throwing up in front of all these people.”+ To the chief hunters, he explained: “It’s her hair, you see. She’s just had it cut for the first time in her life, and she’s not used to it feeling so light. She’ll get used to it.” With that the discussion turned to lighter matters, and the rest of the evening passed in pleasant dining and conversation. Inevitably the wildlings’ table manners left something to be desired, but the villagers were of a mind to make allowances. The sounds and scents of the feast wafted faintly across to the shrine, where Jeylin, Sarlin and Jerrond stood helpless. The head lupinoid Sun had inspected them briefly. Then, satisfied that they were harmless, he had quietly padded away. Under the crystals’ influence they were not able to become angry or depressed, so they silently contemplated their defeat and considered Mavrida’s warning. A little after Sun’s departure, the three men had all become aware of something else; a curious sensation, neither sight, scent nor sound, indefinable and almost imperceptible yet nonetheless real. Whatever it was, it had none of the sorcerer’s heavy-handedness. The men had the impression that they were somehow being weighed, evaluated for some future trial, though by whom or what they could not guess. And then the sensation was gone, leaving them alone with their thoughts. After the feast most of the villagers returned to their homes. For the benefit of the newcomers some of the hunters set to work re-erecting the tents in the centre of the village. The question of permanent accommodation would soon need to be addressed but, as with so many other things, Tolar had decided it could wait for daylight. While Ketrin and Sherinel were helping with the tents, Silverpaw and Shadow returned from their exploration of the village looking chastised. +Are you all right?+ asked Ketrin, kneeling to place a hand on Silverpaw’s shoulder while Sherinel did the same for Shadow. +Big four-leg challenged us,+ replied Silverpaw, referring to Sun. +We both lost.+ +Too bad,+ Ketrin replied, +but it is his territory, after all.+ “Last time they lost,” said Sherinel, “it was to Wenric’s lupinoid brother Night.” He smiled wistfully. “Ah, you should have seen him, Ketrin. He was beautiful. Bigger than Sun and even blacker than Shadow, if you can believe it. He had a temper like you wouldn’t believe, but he fought like a demon in our defence.” Ketrin smiled. “I can see him, Sherinel, in your memories. I’m sorry he died. I’d have liked to meet him.” Sherinel nodded sadly. “In the end it was his stubbornness and pride that killed him. He just wouldn’t take a break and leave some of the fighting to the rest of us. In the end his heart just gave out.” “And yet you tell me he was strong,” Ketrin muttered. “There must have been something wrong with his heart, or he wouldn’t have died so suddenly.” “It hit Wenric very badly,” said Sherinel, “but Scarface is helping him to cope.” While their accommodation was being prepared, Mavrida drew aside with Lendrin and Suvanji, to a secluded spot near the stockade where they would not be overheard. “If we’re to confront the old man again,” she told them, “then I need to ask a favour. I’ve been thinking about it for a while, and I’ve decided that now is the time.” “What favour?” asked Suvanji. Mavrida gave Suvanji a grin that was almost as feral as one of her own, and held up a hand. “Blood,” she said. Shortly afterward they returned to the tent accompanied by Pyrri and Three-Leg. If any of the villagers noticed that Suvanji and Mavrida had fresh bandages on their hands, they made no comment. Mavrida was rapidly becoming drowsy. As soon as the sleeping mats were ready she gratefully lay down beside her friends. She was quickly asleep and dreaming of things that had happened long ago. Some time later Mavrida woke, startled by what felt like hands caressing her body. Reflexively she tried to push them away but her hands encountered only air and the caresses continued: gentle, sensual and arousing. It took her drowsy mind some time to realise that what she was feeling were Lendrin’s hands caressing Suvanji’s body... and also Suvanji’s, caressing Lendrin’s. The blood she had exchanged with Suvanji had given her the ability to share thoughts and sensations. Her friends’ lovemaking was so intense that she couldn’t help feeling every touch... every kiss... every surge of ecstasy... And they were not the only lovers this night. After a time Mavrida was able to perceive, a little further away, Ketrin with Sherinel and Tharil with Wenric. Pyrri and Three-Leg had separate beds, but were clearly aware of and aroused by all of the lovemaking that was going on around them, and sharing the sensations with each other. As much as Mavrida might have wished to remain chaste for the sake of fidelity to Ruthyar, the storm of sensation was making it impossible. Forgive me, Ruthyar, she thought. I mean you no dishonour. Please understand. Then she turned to her friends and sent them a telepathic request, which they eagerly accepted. Eventually the lovers slept. Thunder rumbled in the distance and occasionally came closer, but the lupinoids keeping watch outside the village sensed no trouble that night. With none left awake to witness it, Mavrida’s ring began to glow. Distant observers +Look, J, the neutrino beam just reactivated spontaneously. The presence is using Mavrida’s stone as a catalyst again, only now it looks as if it’s attracted some more presences.+ +The question is, why now, Vandri? All the humans are asleep, and the sorcerer hasn’t begun his endgame yet.+ +I think we’re just going to have to go on trust, J. Whoever or whatever those presences are, they’re definitely not part of the sorcerer’s plan.+ +True enough, Vandri... but they’re not part of our plan either.+ +Oh, so we have a plan now?+ Mavrida and others With Suvanji’s blood still fresh in her veins, Mavrida once more dreamt that she was a lupinoid - or rather, several different lupinoids in succession, male and female, - hunting, mating, fighting and playing. In truth these were not dreams at all. Rather, they were racial memories from countless generations of lupinoids. From such memories, Lupinoid cubs learned survival skills; wildling cubs learned how to be lupinoid without losing the ability to be human; and Mavrida learned how closely lupinoids were tied to the world’s natural cycle. Lendrin dreamt that he was back in his old part of the forest, spear in hand. As he advanced nervously there was a rustling in the bushes before him, and three lupinoids, looking elderly and dishevelled, emerged to stand before him. Instinctively he raised his spear, but the lupinoids stood their ground, neither fleeing nor attacking. A sudden pang overcame Lendrin and he dropped his spear. Sinking to his knees, he breathed: “No. I killed all of you once. I’m not going to kill you again. If you’ve come to take your revenge, then get it over with. I won’t try to stop you.” The largest of the three lupinoids approached Lendrin, but instead of attacking, it merely sniffed him over and then licked his face. The other two took this as licence to follow suit. Weeping partly from remorse and partly from relief, Lendrin hugged the ghosts of the three lupinoids he had killed. “Thank you,” he sighed. Sherinel dreamt that he stood by a stream. As he stared at the rippling waters, a figure emerged to stand before him. It was a boy of eleven or twelve years, whose face Sherinel remembered all too well from when he was a similar age. A tear came to Sherinel’s eye. “I’m sorry,” he found himself saying. “I would have saved you from Borvinn if I could, but I was only a child myself back then. I am so sorry.” The boy spoke quietly, placing a dripping hand upon Sherinel’s shoulder. “Don’t blame yourself, Sherinel. I chose my own escape. It’s I who should be sorry for leaving you to face Borvinn alone. But you face a greater threat now, and this time I won’t back down. Even though I can no longer aid you physically, I can at least help you find the courage you need.” The ghostly figure stepped forward and planted a small kiss on Sherinel’s lips, saying, “I have to leave for a while, but don’t fret. From now on I will never be far from you.” Then he slipped back into the water and was gone. Wenric dreamt that he stood in a clearing as the clouds parted. Barely visible in the light of the moons, a dark figure approached and nuzzled his legs. Wenric crouched down and communed silently with his friend for a while. Their conversation took the form of feelings rather than words. In essence they were a reassurance that though Night was no longer a physical presence in Wenric’s life, some part of him would always remain to assist Wenric whenever his need was greatest. Giving thanks for his spectral presence, Wenric spent the rest of the night dreaming of running, jumping and wrestling with his old friend. Kemmet dreamt he was sitting in the village square when an older man approached him. The man favoured him with the kind of glare one might direct at a venomous lizard, and spoke. “Hear you got your arse handed you by a kid, then let a bunch of strangers talk you down. For Ral’s sake, Kemmet, what kind of son do you call yourself?” “Shut up, old man,” said Kemmet. “You’re to blame for how I turned out.” “Never mind blame,” said his father. “Those strangers have got Tolar’s ear, and this sorcerer they keep talking about is gonna kill everyone in the village thanks to them. So I’ve only got one question for you: what you going to do about it? Better make up your mind, boy. Something tells me you don’t have much time.” Before Kemmet could reply his father’s ghost vanished like smoke, leaving him alone in the square as ominous clouds began to gather. Jeylin, Sarlin and Jerrond did not dream in their paralysed state, but in the absence of sensory stimulus their minds entered a kind of trance in which all things seemed dreamlike. Into their trances, in the darkest hour of the night, came two figures. Shadowy at first, they gained definition and were revealed as a pair of young hunters not unlike themselves. +Who are these people?+ thought Jeylin, and to his surprise the newcomers heard him as if he had spoken aloud. “Oh, we’re nobody much,” said one of them. “Well, we’re literally no-bodies now. Just a couple of helpful ghosts. I used to be Tarvik, and this was Sangrel.” “We died because we were led astray,” said Sangrel, “just as the sorcerer is trying to lead you astray too. Mavrida’s right, you know, the sorcerer doesn’t reward failure.” “True enough,” agreed Tarvik, “but then, he doesn’t reward success either. People are just tools to him, and when he’s finished with them he just throws them away - or worse, hangs them on hooks, figuratively speaking, and leaves them there forever.” “Right,” said Sangrel. “You might be mad at Mavrida for paralysing you, but believe me, this is paradise compared to what you’ll get when the sorcerer’s done with you.” +Why should we listen to you?+ thought Jerrond. “Oh, we were like you once,” said Sangrel. “Cocky. Arrogant. Thought the world owed us favours. And where are we now? Just scattered bones in the undergrowth.” “But at least we died quickly,” thought Tarvik. “The sorcerer won’t give you that much mercy.” “In a day or two,” Sangrel went on, “Mavrida will revive you and give you the option of joining her. Unless you want to spend the next few years paralysed. I suggest you take her offer, and don’t even dream of betraying her or you’ll realise just how right we were about the sorcerer’s gratitude.” With that the two ghosts walked into the mist and were seen no more, leaving the prisoners to their thoughts. Suvanji dreamt that she stood naked in the jungle. She seemed to be looking for something, though she was not sure what. After a moment, however, she became aware that somebody had found her. Turning, she saw a young woman of about her own age, wearing a simple homespun dress that was much the worse for wear. “It’s you,” breathed Suvanji. “You are the presence Mavrida and I have been feeling!” The newcomer smiled and nodded, before tearfully embracing Suvanji. “Daughter,” she whispered in Suvanji’s ear. When the dreamers woke the next morning none of them remembered their dreams clearly, but the emotions they stirred remained with them for some considerable time. Most of them felt comforted and reassured. As for Kemmet, he found himself imbued with a new sense of determination. When the time came he wasn’t going to screw up again. As Kemmet walked out of his hut he almost tripped over Pyrri and Howl. Howl leapt back in alarm and Pyrri growled warningly at Kemmet. Looking her up and down with distaste, he said: “Oh, it’s you. Almost mistook you for a village kid. But if they think they can tame you by giving you short hair and clothes, they’re wasting their time.” Unfazed as ever by his attitude, the wildling simply replied, “Good. Don’t want tame,” before strolling off with her lupinoid. “Pest,” muttered Kemmet. “Wouldn’t let any daughter of mine behave like... Ahh, what am I talking about?” Shaking his head irritably, Kemmet stalked off. Omnes For the next few days life in Third Hill returned to normal. The newcomers helped out with everyday tasks, and in the process the older wildlings began picking up more human words. Erennya was happy to devote her spare time to teach Pyrri and Three-leg about human life and society, and was gratified at how quickly they absorbed new knowledge. She surmised that something in their lupinoid upbringing must have made their minds receptive to information. The rainy season was growing late, and to the villagers’ relief the constant downpours were beginning to ease off a little. However, the approach of the dry season did serve as a reminder that the village’s access to the Hidden Valley was now cut off. Tolar and Tharil discussed the problem at the chief hunter’s residence. “We both know what’s at stake,” said Tolar. “We have to find a way back into that fertile valley before the next drought, otherwise we could all starve.” “Easily said,” said Tharil. “I’ve sent parties out to look for other passages through the cliff, and they haven’t found anything. The cliffs are too high, and in any case we don’t have anyone skilled at climbing.” “Well, what about the stream that Lendrin’s party used?” “Yeah, good luck trying that approach. From what they’ve told us, even if a boat could make it through the inlet gorge it’d take a miracle to find the tributary leading into the Valley - which is pretty much what Lendrin’s crew got. I doubt any of our parties would do as well. And if you could find the outlet from the stream...” Tolar completed the thought: “...then you’d be fighting against the current all the way, and you’d still have the problem of finding the Valley tributary. Well, then, it looks like our only option is to try to clear the tunnel.” “We’ve been trying that as well,” said Tharil. “Trouble is, the collapse has made the surrounding rocks unstable. No sooner do we clear some of the boulders away than more fall to replace them. Telgrin nearly got his arm broken last time. Besides, even if we do clear the tunnel, what’s to stop this sorcerer fellow from blasting it again?” Kemmet, who chanced to be walking past at that moment, couldn’t help but eavesdrop. “And that,” he said, “is exactly why you should send the strangers packing. I keep telling you, but do you listen?” Before waiting to hear their reply the surly hunter strode away. Tolar sighed as he watched Kemmet’s departure. Then a thoughtful look crossed his face. “Send them away...” he murmured. “Now wait,” protested Tharil. “Are you really going to take advice from that backstabbing lout?” “No, Tharil, but he’s given me an idea. You know, my friend, I’ve said it before but it bears repeating: we’re too insular in Third Hill. We’ve practically cut ourselves off from the rest of the world. Now why do you suppose that is, hmm? Is it just the distance from other villages? The difficulty of travelling through the jungle? The danger from predators? Or... is it something else? Tharil was puzzled. “Something like what?” Tolar looked his friend in the eye. “Tharil, what if it’s this sorcerer? What if we’ve all been influenced by him somehow. not just us but people all over the forest... to become afraid of travelling? Even afraid of our neighbours? To become isolated from the rest of the human race? It’d be a lot easier for him to conquer a lot of isolated villages than an integrated community, wouldn’t it?” Tharil considered his words. “Well,” he said, “that could explain why the striagons are so aggressive these days. The sorcerer’s controlling them, using them to try and keep us from travelling, joining forces, ganging up on him. Although if he’s really as powerful as he seems now, I don’t see how that would help.” “Be that as it may, we could at least try. And if in the process we find somebody we can trade with for food, so much the better. So say we just modify Kemmet’s idea a little - we send the newcomers away on a mission. A mission to find and reunite the peoples of the forest. And if they also happen to come across any new wildlings who could help, that would be a bonus.” Tharil nodded thoughtfully. “It would also divide the sorcerer’s attention, for what it’s worth.” When Mavrida’s party heard the suggestion, they had mixed feelings. Mavrida felt it would be foolish to split up again so soon after coming together, and Lendrin agreed. Sherinel, on the other hand, was more enthusiastic. “The obvious place to start would be Jezrin’s village,” he said. “I think by now we must have convinced his hunters of our good intentions. Ketrin and I could accompany them back there and plead Third Hill’s case.” Lendrin said, “What do you think, Suvanji? Should we also go, maybe try to find other allies?” The wildling had been staring vacantly into the distance, as if listening to a voice from afar. Lendrin’s voice seemed to break her trance and she spoke hesitantly. “Yes... yes, I think we must,” she said. “Must?” “Yes, Lendrin. I felt the presence in my mind again. I think... it’s telling me there’s something I need to do, somewhere I need to go, and we can ask help for Third Hill at the same time.” “Well... do you know what it is you have to do? Do you have any idea?” “No,” she replied. “The presence didn’t speak in words, just feelings... but it did give me a direction, and I’m sure I’ll know what to do when we get there.” Lendrin considered this for a moment. “All right, then,” he said. “You trust your instincts, and that’s good enough for me. Where you go, I follow.” They turned to Mavrida expectantly, but she merely sighed. “I’m sorry, my friends. I think I should stay here and help look after Pyrri and Three-Leg. They’ll want to go with you of course, but it would be better if they stayed here in the village.” Ketrin, who had been listening quietly to their deliberations, said, “If Lendrin and Suvanji are going on a journey of their own, they’ll need more than just Nipper to help defend them. I think Keino, Wenric, Ash and Scarface should go with them. Sherinel and I will have Silverpaw and Shadow as well as Jezrin’s hunters Velleth and Rilshan. That’ll leave Red, Grey, Howl and the twins to help Sun and Fire defend the village.” “Well,” said Lendrin, “if we’re going to do this we should do it as soon as possible.” “Then it should be today”, said Ketrin. “We’d better prepare and say our farewells now.” They all nodded and set off to do so. The adult wildlings and companions And so it was that later half the village turned out at the lower gate to watch the two parties depart. Tolar made a short speech wishing them luck, Therys and Erennya hugged Suvanji, Mavrida, trying to hold back tears, hugged all of her friends, saving her son for last and longest. Pyrri and Three-Leg watched jealously, and Kemmet muttered “Good riddance” under his breath. Pyrri, overhearing this, said “Old grump,” and neatly sidestepped a blow before Erennya hustled her away and favoured Kemmet with a scowl. The presence in Suvanji’s mind was steering her in a northerly direction, very close to the route back to Jezrin’s village. It would therefore be some days before their courses diverged, so both groups set out together. The villagers’ cries of good fortune followed them until they reached the treeline. Keino and Wenric were initially a little wary of Lendrin and Suvanji, having had only the briefest acquaintance with them, but thanks to their telepathy they and their lupinoids were soon at ease. Ketrin knew Suvanji quite well, since they had conversed telepathically many times while he sat in his shrine, and she had told him a great deal about Lendrin. The rest now had a chance to make their acquaintances while travelling, and this was greatly facilitated by the fact that most of them were telepathic. The only exceptions were Rilshan and Velleth, who reiterated their request to have the gift conferred on them. “All right,” said Sherinel. “I promise we’ll give you telepathy. But it does make you drowsy for a while, and it’s best you remain alert as long as we’re in the forest. Once we get to your village, then we’ll do it. All right?” The hunters had to be content with that. Since they would be out of human contact for several days Ketrin and Lendrin decided it would do no harm to let the wildlings go naked, and the villagers decided they might as well do the same. If any humans met them en route, they would just have to accept it. Each night the two groups took separate sleeping arrangements. Ketrin and Sherinel formed a male foursome with Rilshan and Velleth. Ketrin and Sherinel had a lot of catching up to do, but Sherinel didn’t mind sharing him with the hunters. After all, Ketrin had been shared by the whole of Third Hill for a year, so it was a little late for jealousy. Meanwhile, Keino was keen to share what she had learned about human sex with Lendrin, and likewise Wenric with Suvanji. In their case, jealousy was pointless when all of them could feel each other’s sensations. Later, Keino embraced Suvanji, and Wenric approached Lendrin. Lendrin was a little reluctant at first, having never experienced sex with another man, but at the same time he didn’t want to hurt the wildling’s feelings by refusing. He compromised by allowing the wildling to embrace him as long as no form of anal penetration was involved. (Even so, the telepathic overspill from the male foursome gave them both a very good idea what it felt like anyway.) In the event, they soon found many other ways to give each other pleasure, and Lendrin had a feeling he might get used to them. Inevitably, the combined party faced several striagon attacks, but faced with eight well-armed humans and five lupinoids, the conflicts were one-sided and the defenders only suffered minor injuries. Eventually the time came for the two groups to go their separate ways. Sherinel said farewell to Keino and Wenric, and ordered them to keep Lendrin and Suvanji safe. Then Ketrin’s party continued northward toward Jezrin’s village, while Suvanji guided hers a little further to the east, skirting Jezrin’s village, and then northward once more. Kemmet and Pyrri Back in Third Hill daily life resumed its normal routine. When they were not hunting the menfolk spent much of their time honing their weapon skills. Kemmet quite enjoyed archery practice, since it was one of the few times the other villagers weren’t whining about his attitude. Whatever else the ungrateful bastards might say about him, they could never accuse him of neglecting his bowmanship. On the second day after the two groups’ departure Kemmet was feeling particularly good about himself and life in general. The rain had eased off to the point where there were even a few dry spells and, at a range of thirty cubits, he had just scored his third vornseye. Then he heard the humming... “Hey, Kemmet,” laughed one of his fellow archers, “Looks like your girlfriend’s here.” Pyrri strolled up to the archery range with Howl in tow. Pyrri was half-humming, half vocalising, a song that Erennya had taught her. “Oh, great,” muttered Kemmet. “And it was such a nice day too.” The wild girl paused by Kemmet, looked across to the straw target in which his arrow had just landed dead centre and said “You good.” “Don’t need you to tell me that,” he grunted. “I’ll say one thing, though. Your singing isn’t quite as irritating as it used to be. Still doesn’t mean I want you hanging around like a stale fart, though.” Pyrri pointed to Kemmet’s bow, saying, “I wanna learn.” Kemmet was incredulous. “You? Archery? What’s the point? Women don’t hunt.” “S’vanji hunt. She wildlin’. So’m I. She can hunt, I can hunt.” Kemmet snorted. “Yeah, well, even if Tolar lets you hunt, who’s gonna train you?” By way of reply, she simply stared at him with her feral grin. Meanwhile Howl yawned and scratched himself. “Oh, you have got to be joking,” Kemmet groaned. “Tolar say you best,” she said. “He say,” (here she lowered her voice in imitation), “ ‘Kemmet may be real miser’ble... ’ then he say word, don’t know what it mean... ‘but he best damn archer we got.’ I wanna learn best, you teach.” “For Ral-ne-Sa’s sake,” he sighed. “You’re a persistent little bugger, ain’t you?” “That it,” she told him. “That word Tolar say.” “Huh. Takes one to know one, eh? And I suppose you’re never going to stop pestering me unless I do it.” “Nope,” she agreed cheerfully. Kemmet emitted a longer sigh and ran his hand over his face. “All right. All right, you little brat, listen up. I’ll do it...” Pyrri’s grin widened, which only caused his scowl to deepen. “...I’ll do it, if Tolar gives his permission.” “Awright.” “But you listen, and you listen good now. If he does, then you damn well better learn. I will not allow you to waste my time. You will show up for lessons and not run off to play with that four-legged fleabag of yours, and if I think you’re slacking at any time, then, wildling or no wildling, I will take it out of your hide. Understand?” Unmoved by his attitude, she simply nodded. “Yeah. Un’erstan’. I learn.” “And while you’re at it, learn to talk properly. You’re gonna drive me crazy with that damn baby-talk of yours.” “Awight,” she said. “I go learn what them words they say ’bout you mean.” The wildling resumed her song and sauntered off as casually as she had come, with Howl padding after. “Now look what she’s got me into,” muttered Kemmet. “How in the nine hells did that little twerp con me into agreeing?” In an attempt to regain his composure he loosed another arrow, then growled in frustration as it buried itself in the outer ring of the target. Suvanji’s Party Suvanji’s party pressed on northward, fending off only one further striagon attack after leaving Ketrin’s group. +Do you know how much farther we have to go?+ asked Lendrin. +I think we should be there by tomorrow afternoon,+ she replied. +All right. Let me know when we get close - we mustn’t forget to put our clothes back on!+ Sure enough, it was a little after noon the next day when they came to an artificial clearing with a stockade at its centre. They were soon approached by two sentries armed with spears. Ordering the lupinoids to hang back, Suvanji and Lendrin approached the guards with their own weapons lowered. They had not forgotten to put their clothes back on, but upon seeing their purple eyes the sentries regarded them as warily as if they were wild lupinoids. “Who are you and what’s your business here?” said the first sentry. “We’re from Third Hill, Tolar’s village to the south,” Lendrin informed him. “We have come with a request from Tolar to open trade between our villages, and Suvanji here has an errand of her own that she’d like to discuss with your chief hunter.” The sentries drew aside to confer. After a moment the one who had spoken previously said, “All right. I guess Ralvin will hear you out, at least.” Suvanji thought Ralvin’s name seemed oddly familiar, but she couldn’t think where she might have heard it. “Your animals will have to wait outside,” said the lead sentry, “but if the chief decides you’re all right he’ll probably spare some food for them - and you too.” “Fair,” said Lendrin, ordering the lupinoids to wait and keep watch outside the stockade. Then the sentries led the humans through the gate and into the village. As they were walking toward the chief hunter’s residence, Suvanji halted in her tracks and the breath caught in her throat. +What is it?+ thought Lendrin, as the guards (perhaps suspecting a trick) asked the same thing aloud. “It’s nothing,” she said. “I caught my foot on a stone.” In truth, she had suddenly remembered why the name Ralvin sounded so familiar. Ordering the strangers to wait outside, the sentries disappeared into the chief’s hut. They re-emerged a few moments later and motioned them to enter. As she followed Lendrin into the hut ahead of the other two wildlings, Suvanji’s heart was racing. The hut was occupied by a tall man of about forty years with a neatly-trimmed beard, and a woman who appeared a little younger. “Welcome to our humble village,” the man said. “As you’ll have gathered, I am chief hunter Ralvin. My wife, Tajumi.” Tajumi inclined her head in greeting. “So,” said Ralvin, “what business brings you here with three lupinoids at heel?“ Lendrin briefly introduced himself and his friends and went on to outline Tolar’s proposal to reunite the villages, and the reason behind it. “A sorcerer, controlling striagons?” said Tajumi. “It all sounds a bit far-fetched, doesn’t it?” “But,” her husband replied, “now I think about it, the striagons have become more aggressive these days, bolder in their attacks. Almost as if something was controlling them. Tell me, Suvanji, that scar on your arm - was that caused by a striagon?” “Oh, no, chief hunter,” she said. “That was an... accident. If we have time I’ll tell you all about it later.” After a moment Ralvin told his visitors, “You may as well know, I am not originally from this village. Many years ago I left my old village and made my way through the jungle. I wasn’t even sure of my destination, only that there must be some friendly village that would take me in. “The way was perilous, with no clear paths, and I was convinced that a striagon or lupinoid was going to eat me before I could reach safety. Then one day my worst fear seemed to come true when a striagon broke cover and charged. But then, before it could reach me, something else emerged from another part of the undergrowth and headed it off.” “A lupinoid?” said Lendrin. “Saved my life,” said Ralvin, nodding. “Between us me and the lupinoid managed to finish off the striagon. Once it was dead I knelt down in front of my saviour and said, ‘Does this mean we’re friends now?’, and he licked my face. “Well, needless to say I was amazed. People from my part of the forest had always thought lupinoids were as mindless and aggressive as striagons, but here was one that was actually willing to protect me, a complete stranger, and two-legged with it.” He chuckled. “Whether I should take that as a sign of intelligence or stupidity I don’t know, but we travelled and hunted together after that. Some time later we found a decaying old bridge across the river, and eventually made our way here.” “Yes, we know of the bridge,” said Lendrin. “Our two wildling friends here saved a man from falling, before the bridge finally collapsed.” “So there’s no way back across the river?” said Ralvin. “Ah, well. I was never that nostalgic for my old home anyway. But the two of us eventually made our way here and the villagers took us in - out of pity, I suspect. I begged them not to kill the lupinoid, and that’s when I found to my relief that folk in these parts are better-disposed to the beasts.” He sighed. “Killer hunted at my side for the rest of his life. When he got too old and sick... well, I couldn’t let him suffer. And now he lies beneath the tree in the court, while here I sit in charge of the village hunt.” Ralvin sighed quietly as a nostalgic smile played upon his lips. “You know, he’s been gone for more than ten years, but I still feel as if a part of him is still watching over me, guiding and protecting me.” Suvanji nodded slowly. +This is all very well,+ Lendrin projected to Suvanji, +but it doesn’t tell us if he’s willing to help.+ +Patience,+ she replied. +It tells me everything I need to know about him. I think he’ll help.+ “Well, I imagine you’ll be hungry after your journey. Let’s discuss your proposal over a meal. Your lupinoids are welcome to join us as long as they don’t get too excitable.” “Don’t worry, we’ll keep them in check,” Lendrin assured him. Ralvin summoned the sentries to fetch food and drink, while allowing Lendrin to open the gate for the lupinoids. Then the humans sat down to dine in the hut. It was a simple midday repast - slices of spiced, raw vorn meat with local vegetables, and blocks of a pungent-smelling substance made from fermented milk that Ralvin identified as “cheese”, all washed down with mugs of ale. Lendrin sent a telepathic caution to Keino and Wenric against drinking too much. “If I may ask, chief hunter,” said Suvanji, “what was it that made you decide to leave your old village?” A shadow crossed his face. “Ah, well... that’s a sad story. An innocent girl and her child lost their lives, and I have to take at least some of the blame for their deaths.” “Ralvin,” said Tajumi, “do you really think this is the time or place to discuss such things?” Placing a hand on her shoulder he said, “They have a right to know. And besides, it always helps to get it off my chest.” Turning back to Suvanji he continued: “You see, in my youth I fell in love with a girl, but her parents didn’t approve. But we kept seeing each other anyway and one thing led to another, and... we were careless. She became pregnant. When her parents found out, of course, they were furious. Threatened to kill me and kept their daughter a virtual prisoner in her own home. “Well, at least they didn’t try to end the pregnancy. If they’d tried, it might have killed her anyway. I think they had some idea of giving the child away once it was born, or even selling it. “They wouldn’t let me anywhere near her of course, otherwise we’d have run away together. As it was, the last I heard of her was that she’d run off into the jungle by herself. As soon as her parents found her missing the hunters were sent to look for her...” He sighed heavily. “They came back two days later, carrying her... what was left of her... in a sack. They said some animal had been feeding on her, but they couldn’t tell if that was what killed her.” “And that’s when you ran away,” said Suvanji. “Yes. I felt like I deserved to join her - that if I got eaten too it would somehow redress the balance. But when Killer saved me from the striagon, I realised I was wrong. I almost felt that she was guiding him somehow, that she was telling me there was no point in our both dying. And every day since I’ve prayed that she would approve of the way I’ve lived my life.” Looking at Suvanji, he said, “I’ve always wondered what our child would have been like. I suppose it would have been about your age now, give or take a year or two.” Suvanji gave a half-smile. “Well, Ralvin... I am a year or two older than I look.” Ralvin was taken aback. “Wait,” he said. “S-suvanji, you... you can’t be suggesting - ?” “The girl,” she said quietly. “Her name was Shendra, wasn’t it?” The look on his face was confirmation enough. “How... how could you possibly... I’ve never told anyone her name.” “Ralvin,” she said, “I can’t explain how I know, but I do know it’s true. Shendra gave birth in the jungle. She knew she was too weak to survive, but some power - a god, perhaps - answered her prayer and saved her daughter’s life. Lupinoids found her daughter and raised her as a woman-cub - a wildling. For many years she ran and hunted with her pack in the forest. Until one day she met humans, and they taught her to speak - and they gave her a name.” “Suvanji,” he breathed. “Then... then you...” Tajumi turned an astonished glance from Suvanji to Lendrin. “Did you know?” she whispered. Lendrin could only shake his head dumbly. As if with fresh eyes Ralvin took in the sight of the tall, self-confident young woman who sat before him and stammered, “C-can it... can it really be possible? Suvanji, are you truly Shendra’s daughter?” “Yes,” said Suvanji. “Yes, Ralvin. I know I am. I think... somehow Shendra’s spirit has guided me to this place, so that we could meet at last.” Ralvin hesitated only for a moment, then stood, motioned Suvanji to stand before him, and gathered her into a fierce embrace. “Father,” she sighed. March 2013 - September 2014

|

In our next unexpected instalment:

THERE WILL BE A KETRIN PART FIFTEEN. THAT’S ALL I KNOW.

Comment on this story | Return to Top of Page | Home