Site Introduction | Art Gallery Index

The Singer | Applause | Folly | Peace | Topless Female Statues

Shelley Memorial | The Snowdrift | Linos

| Egyptian girls | ||

|  |  |

(1852-1901)

The Singer and Other Works

Revised and updated September 2010, August 2011, May-July 2013 and August 2014

This page has been massively expanded with new photos, and it ain’t quite done yet..

STILL TO BE ADDED: some photos of the Edward Onslow Ford memorial in London.

PS: If you came here searching for Ford cars you’re in the wrong place

The Singer | Applause | Folly | Peace | Topless Female Statues

Shelley Memorial | The Snowdrift | Linos

Introduction

Skip Introduction

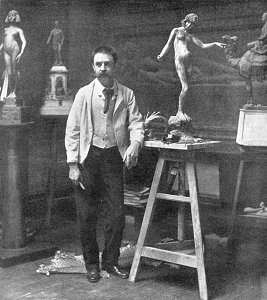

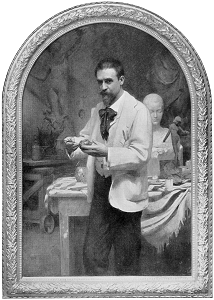

The Late Mr. Onslow Ford

The Late Mr. Onslow FordThe sudden death of Mr. Onslow Ford at the age of forty-nine is an event which gives one pause in the rush of contemporary life. As a near neighbour of Mr. Ford’s in St. John’s Wood I had many opportunities of recognising his kindly, genial nature; it was further a delight to talk with him on any subject pertaining to art or literature. His work, moreover, was so exceedingly varied; it included presentations in every branch of the world’s work; now he had for a sitter a member of the Royal Family, now a great general, and perhaps another day a distinguished actor... It was sometimes difficult to realise that Mr. Onslow Ford was an Englishman; he had at times well-nigh the appearance of a Spanish grandee.

--Gossip of the Hour, The Tatler magazine, No. 27, January 1, 1902.

Who can describe this gentle and amiable man? With the allure of the garçon du Quartier Latin, although I believe he studied only for a short time in Paris, his inner personality was that of a true-born, loyal Briton, with that intense love of home and of family life which is characteristic of the race. He was all his life dominated by two strong affections - love of his family and love of Art; and, as is usual where a man is not single-hearted in his loves, jealousies and conflicts occurred between the rival passions. But he was strong and patient in the depths of a nature that on the surface was so frail and fragile, that it vibrated like the leaves of an aspen at each breath of wind or touch of sunshine.

He was born to enjoy much, and to suffer much. His life was comparable to the ever-restless seas that pass from buoyancy to calm, and from calm to storm, under the changing moods of mobile skies. We met in early life, and we walked side by side in joy and in sorrow until he died, nearly twenty years ago. He moulded his Follies and his Singers, “little waxen figures,” as a “friendly critic” once called them, and I limned my little portraits of big men; and we both were happy at our work and in our homes.

John McClure Hamilton, Men I Have Painted, 1921

Edward Onslow Ford was one of the most highly-respected members of the so-called “New Sculpture” movement of the late 19th century, and I’ve gone out of my way (literally) to find and photograph as many of his nude works as humanly possible. You’ll find many of the results on this page, with more to follow.

Sadly, like his near-contemporary Harry Bates, Ford did not live to see the age of 50. The exact cause of his death was never made public, but there is a suggestion that he may have committed suicide due to financial problems. Because of the massive stigma attached at the time, suicide was seldom publicised. If so, it’s a tragic end to a brilliant career.

It’s a token of the respect in which he was held that his widow received dozens of letters and telegrams of condolence, including from such contemporary sculptors as Albert Toft, Alfred Gilbert, F. W. Pomeroy, William Goscombe John, Thomas Brock and George Frampton, as well as painter Arthur Hacker, and also one Maria Bates, presumably Harry Bates’s widow.

Some of Ford’s statues spend most of their time locked away in basements, which I have always believed is a criminal waste. Consequently I was only ever able to view them in the form of photographs, some of them almost a hundred years old, or not at all.

Some of Ford’s statues spend most of their time locked away in basements, which I have always believed is a criminal waste. Consequently I was only ever able to view them in the form of photographs, some of them almost a hundred years old, or not at all.Then in the summer of 2010 the Tate Britain Gallery in London had an apparent rush of blood to the head, and opened a (sadly temporary) display area for “The New Sculpture” of the late 19th century. This included three of Ford’s statues, along with Pandora by Harry Bates. I was thrilled to be able to meet some of my favourite statues in the flesh (so to speak) for the first time, and I wasted no time photographing them in the round, including many angles that weren’t in the official photos. Conditions for photography were less than ideal (glass cases, artificial light and a total ban on flash), resulting in some grain, soft focus and stray reflections. Nonetheless, I don’t think my pictures came out looking too horrible, and you can now view the best ones here.

Versions of some of my photos here have also been posted on

my Flickr account, under the username Ketrin1407

(mostly before Flickr’s two idiotic redesigns).

The Singer (1889)

Found photos

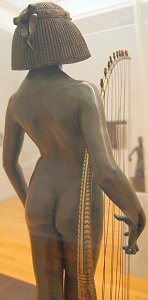

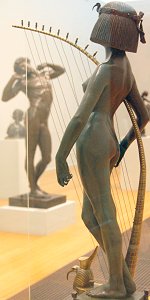

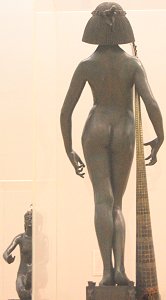

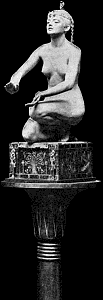

An Egyptian girl, naked but for a headdress, stands beside a tall harp...an image that, together wiith Albert Toft’s Spirit of Contemplation, inspired my adult story “The Singer”. Do not follow this link if you find erotic content offensive.

Astonishingly, these four photographs were the only pictures of The Singer that I was ever able to find, apart from a couple of tiny images accompanying its official description on the Tate website (a few more have appeared there since then, accompanying a special feature about The Singer and Applause). Even from these few pictures it was clear that The Singer, with its beautifully observed figure, ornate decoration and gilding and carefully strung harp, was a remarkable piece of workmanship. Even so, seeing the real statue for the first time gave me an even greater respect for Ford’s skill.

Tate Britain Gallery, London

New Sculpture exhibition, August-September 2010

| The following 30 photos are by Leem. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify these images under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation license, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license can be found in the Wikimedia Commons entry “GNU Free Documentation License”. |

Astonishingly, for most of its life The Singer’s polychrome glory was hidden beneath a layer of uniform brown varnish, which was apparently still there when the vintage black and white photographs above were taken. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the Tate’s restoration experts removed the varnish, and through painstaking research into Ford’s original materials and methods were able to restore the original colour scheme. Judging by the vintage photographs a couple of small features have been lost to the ravages of time: the curled spike on the ibis’s crown at the base of the harp, and a feature at the tip of the harp itself. These ommissions don’t really detract from the statue’s aesthetic value, though it would be nice if they could be replaced.

The statue originally stood on a tall pedestal so that viewers had to look up to see her face. In the 21st century she just has to make do with a glass and plastic display case like all the other Tate statues.

Thanks to the Tate’s restorers, we can admire all the detail that Ford lavished on the creation of this statue. As well as all the multicoloured decoration on the harp, every string has to be precisely placed so the girl appears to be playing it. The fabric of the girl’s headdress is precisely delineated; her metal coronet is also finely-detailed and set with coloured stones. Even the ibis-head decoration at the front has realistic mottling on its skin, while the ribbon at the back falls in convincing folds. And that’s before I even mention the other ibis decoration at the base of the harp with its pharaonic headdress and crown, or the patterned reliefs on the statue’s pedestal. The figure of the girl herself shows the same precise attention to detail not only in its modelling but in the way her expression, pose and body language capture her intense concentration and nervous energy. All in all, I might dexcribe The Singer as a tour de force of the sculptor’s art, if I were the sort of person who used pretentious phrases like that.

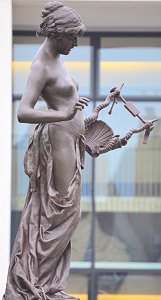

Applause (1893)

Tate Britain Gallery, London

New Sculpture exhibition, August-September 2010

Walk Through British Art: 1890 Room, December 2012

| The following 31 photos (excluding the black and white engravings, which are public domain due to their age) are by Leem. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify these images under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation license, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license can be found in the Wikimedia Commons entry “GNU Free Documentation License”. |

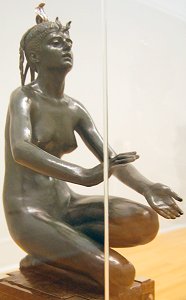

This 1893 companion piece to The Singer doesn’t seem to appear in many vintage art books, at least not the ones where I found the older photos of The Singer. Unlike The Singer, which was part of the original Tate collection, Applause used to be privately-owned and was hardly ever displayed. She was later acquired by the Tate and, her appearance there in the summer of 2010 was a rare opportunity for me to photograph her. Admittedly these images suffer from the same problems as my other Tate pictures, but apart from one small image on the official Tate website and a few more on Flickr, these were for a time be the only photos you could find of her anywhere. Finally in December 2012 she went back on permanent display at the Tate’s BP Walk Through British Art galleries - though frustratingly, The Singer has not been put back on display with her. One of the following shots (see if you can spot which one) was taken while the room was being prepared, before she was put back in her glass case. As for the rest, by using a wide angle lens, and wearing dark clothing and gloves, I was able to avoid some of the reflection problems I’d previously experienced with the glass, although in some views the wide angle makes her hands look freakishly big.

Some rare old engravings show the statue on a tall pedestal, just like her ‘sister’. It would be fascinating to see the two statues displayed that way, but I guess it wasn’t practical, even assuming the pedestals still exist.

As you can see, this girl also has a headdress and coronet, this time decorated with cobras (representing the Nile, apparently), and also sits on a sculpted pedestal. Although not as finely-detailed as The Singer, there’s still a lot to enjoy about this piece.

This is a contrast-enhanced photo of the rear of the pedestal, showing two statuettes of Egyptian goddesses, and a hidden image that hopefully shouldn’t be too hard to make out...

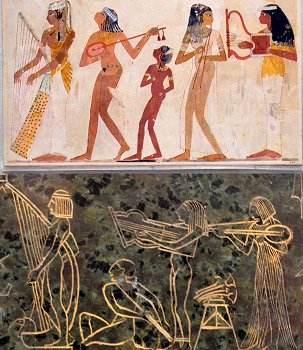

Amongst the Egyptian-style engravings on the sides of the pedestal (the left side is a mirror-image of the right) are two figures, one of which looks suspiciously similar to Applause herself, and the other of which is indubitably The Singer. The engraved Singer seems to have been promoted to lead singer in the band. Good for her.

Finally, here’s a comparison between a real panel from an Ancient Egyptian tomb painting, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the top row of musicians on the base of Applause. Note the similarities between the clothing (what there is of it!), decoration, headdresses and musical instruments, demonstrating that Ford had done some research on his subject.

Dating from roughly the same period, French sculptress Jeanne Itasse’s statue Egyptian Harpist uses similar subject matter to Ford’s Egyptian girls. Unfortunately I’ve only been able to find one vintage photo of it, and it’s possible that it may not have survived the upheavals of the 20th century, which would be a shame.

Meanwhile, rounding off this look at the two girls, here’s a comparison of their faces in profile. You’ll notice that in both cases the camera chose to focus on the foreground, so their headpieces came out sharper than their actual faces.

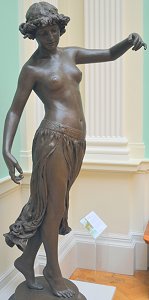

Folly (1886)

Tate Britain Gallery, London, August-September 2010.

| The following 7 photos are by Leem. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify these images under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation license, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license can be found in the Wikimedia Commons entry “GNU Free Documentation License”. |

The spirit of Folly stands on the edge of a cliff beckoning us to follow.

And all too often, human nature being what it is, we do...

This was the only Tate statue by Ford I got to photograph that wasn’t in a glass case. There were still a few focus and exposure issues, but I don’t think the pictures came out too bad under the circumstances.

With none of the ancillary decoration of the other statues this is by far the simplest of the three Ford works on display, but no less assured in its command of facial expression and body language.

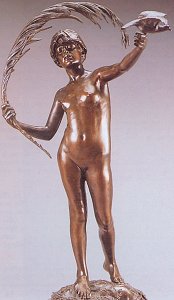

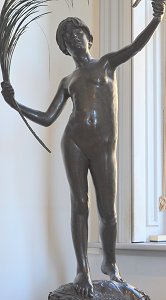

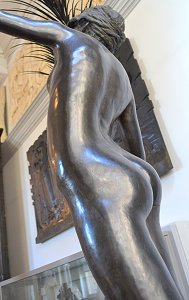

Peace (1887)

Found photos: old book engraving and three bronze reproductions

(1) Bronze statuette, colour (2, 3, 4) Lifesize bronze at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, Flickr images; two by Sam the Sham and the Photos, December 2007, and one by Sheepdog Rex, January 2012

The figure of Peace holds an enormous palm frond and releases a dove - except in the upper left-hand bronze version, where the bird has evidently flown (possibly into the hands of an art thief). Speaking of Ford’s command of facial and body language... in this piece the girl’s face wears an expression of almost ecstatic euphoria. Given her tender years, maybe it’s best not to explore that in any great detail. The two pictures at bottom centre and right are from Flickr, with links to the relevant pages. They were taken at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. I subsequently visited Liverpool myself, and my own photos of Peace can be seen below.

| The following 9 photos are by Leem. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify these images under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation license, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license can be found in the Wikimedia Commons entry “GNU Free Documentation License”. |

Topless Female Statues

Remastered versions of old book engravings plus various others

Knowledge (c. 1898) (left) depicts a girl reading from a scroll on her lap. Several other sculptors used scrolls to symbolise knowledge: Albert Toft’s statue Education (picture not yet available) and Alfred Gilbert’s Mother Teaching Child (1881) (also shown at the Tate’s 2010 New Sculpture exhibition) (Flickr images) both depict parents teaching their children from scrolls, while elsewhere in this very Gallery you can see French artist Charles Jean Marie Degeorge’s statue of the young Aristotle looking very

I have no idea why the original versions of Music (second from left) and Dance (third from left) (both 1890) are wearing birds on their heads. I seem to recall reading that the originals had gone to India not long after they were completed. There were a number of bronze reproductions, which perhaps wisely discarded the bird hats. (Second right: bronze statuette of Dance; right: life-size bronze version of Dance in the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight, Merseyside, UK, taken by mrmaclear on Flickr.) Another bronze copy of Dance found its way to the US via Germany. PBS’s Antiques Roadshow caught up with it in Wichita, Kansas in July 2008 and gave it an insurance value of US$20,000.

Dance: above, four views of a statuette (not the Wichita version). Below, my own photos of the lifesize version, next to the door of the Lady Lever Art Gallery.

| The following 19 photos of the next two works are by Leem. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify these images under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation license, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license can be found in the Wikimedia Commons entry “GNU Free Documentation License”. |

As for Music, I discovered that there is a variation entitled The Muse of Poetry which stands near the Marlowe Theatre in Canterbury, as part of a memorial to the eponymous Christopher Marlowe.

Shelley Memorial (1892)

Various images from around the web

One of the few nude statues by Ford that I haven’t actually seen or photographed, the memorial to the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822, if anyone cares) was erected at University College, Oxford 70 years after his death, having been commissioned by Shelley's daughter-in-law, Lady Shelley, and depicts Shelley’s body after his drowning. Yeah, there’s that Victorian obsession with death again, which we’ll we see again in the next work depicted...

The Snowdrift (1901)

| The following 11 photos are by Leem. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify these images under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation license, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license can be found in the Wikimedia Commons entry “GNU Free Documentation License”. |

One of Ford’s last works, exhibited posthumously, now in a glass case at the Lady Lever Art Gallery, depicts a nude girl lying asleep, dying or dead in the eponymous snow. The statue has a splendid base incorporating veined blue marble, but the base may be the posthumous artist’s work.

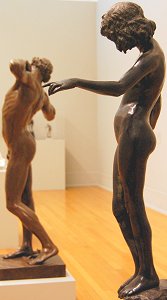

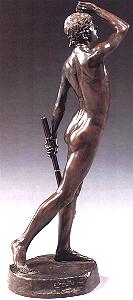

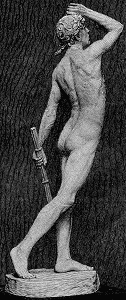

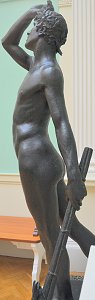

Linos (1884)

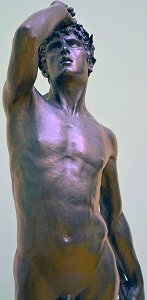

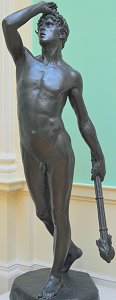

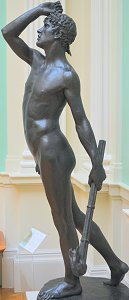

Five views of Linos (or Linus...no relation to the Peanuts character!) - three side views of bronze reproductions, including one line engraving from an art book, and a front view with fig leaf added. The artist’s signature can be seen on the base in the big version of the left-hand image. The inscription on the front of the base in the third from left image reads

Four views of another statuette version. Once again Ford’s signature can be seen on the base in the right-side view.

Linos seems to have been a Greek god of melancholy. His expression, gesture and lowered torch seem intended to convey his feeling of dismay, although with a body like that you can’t help wondering what he’s got to be so miserable about.

Some more views of a statuette version, this time at the Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum, Saginaw, Michigan.

On this version the artist’s signature is on the top of the base in the right-side view.

Below are my photos of the full-size version at the Lady Lever Art Gallery, on the opposite side of the entrance from Dance.

| The following 6 photos are by Leem. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify these images under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation license, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license can be found in the Wikimedia Commons entry “GNU Free Documentation License”. |

The End

Comment on this page

Site Introduction | Art Gallery Index | Return to Top of Page